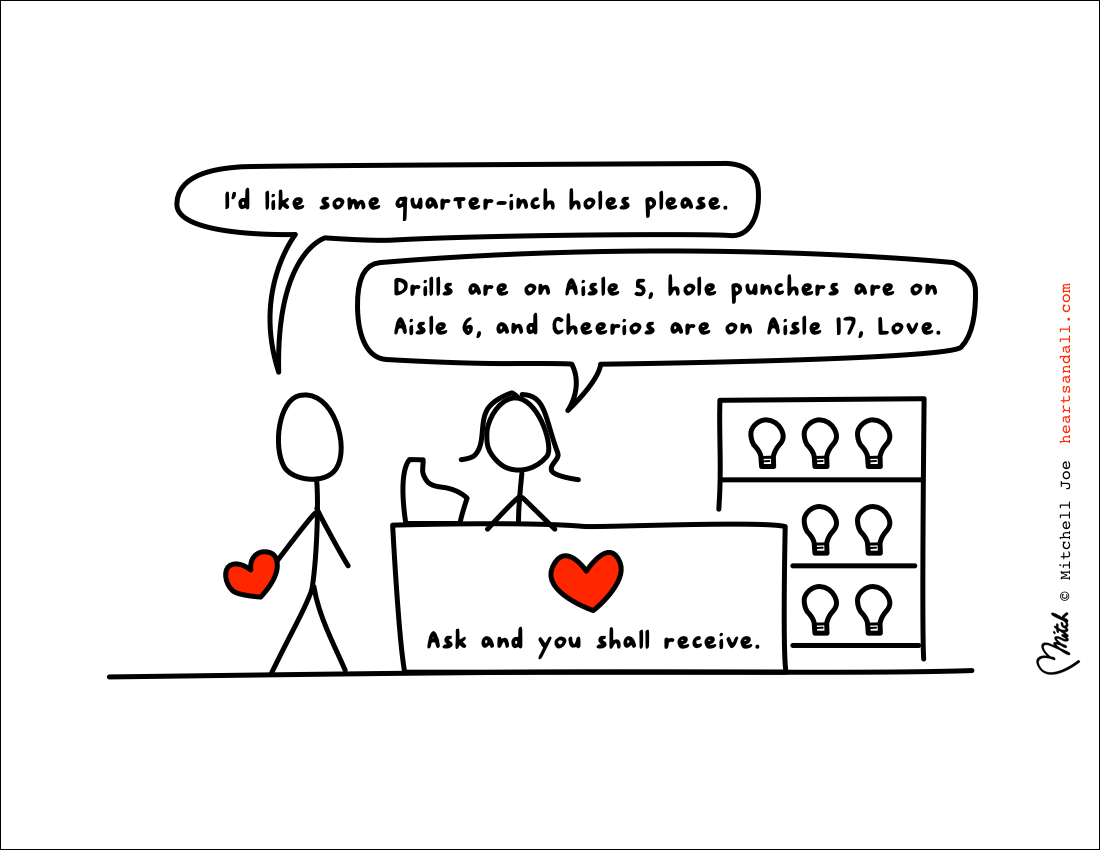

Leo McGinneva put it this way: “They don’t want quarter-inch [drill] bits. They want quarter-inch holes.” His point is that someone who walks into a hardware store to buy a drill and a ¼” drill bit doesn’t really want either of those things—what the shopper really wants is ¼” holes to be somewhere where they aren’t yet—and if you could sell her those, that’s what she would buy.

It’s a good practice to look at anything that you desire and ask yourself, “Why do you want what you want?” If you want the thing for its own sake, like going to the beach to swim in the ocean and feel the sand beneath your feet, then you’ll probably know that that’s why you want it. But if it’s something that you want for the sake of something else, like wanting money to be able to afford a certain type of lifestyle, then it might be harder to realize when you have solved your problem or reached your goal and when you should stop. But why work until you’re 65 if you only need to work until you have a million dollars? With the example of money, it makes more sense to work until you have a certain number of dollars rather than until you are a certain number of years of age.

Let’s say you want a banana. Why? If it’s because you like the way they taste, then that’s fine and we’d probably leave it at that, but if it’s because you want to be healthy, then you have to ask yourself: Is there anything you could eat that’s even healthier? If it’s because they’re cheap, then you have to ask yourself: Is there anything that’s even cheaper? If it’s because they are easy to peel, then you have to ask yourself: Is there anything else that’s even easier to peel, or something that requires no peeling at all?

Here’s some big picture inspiration for you. You can catch a monkey by putting a banana inside a box with a hole big enough for the monkey’s empty hand to enter but small enough to prevent the monkey’s fist from leaving the box while it’s clutching the banana. Monkeys have forgotten the big picture. They will lose their life or freedom over one meal. On the other extreme, you can catch a fox with a steel-jaw clamp that springs shut on their paw when they step on it. But if you don’t check your fox trap fast enough, you will find that you will have lost your fox—because foxes will chew off their own leg and leave the trapped paw in the trap in order to escape with their life. A fox will trade a foot for its life and freedom any day that it has to. Foxes know that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, that sometimes weakness is good, and that sometimes the link that you need to break isn’t on the chain. Don’t be a monkey. Think like a fox.

I saw a surfing video of someone who was riding a wave on a surfboard, then fell off his board, and continued to ride the wave, on his belly, bodysurfing without his board. If your goal is to ride the wave as long as possible, then a board isn’t necessary.

In a soccer match between USA and Egypt (in 2009), American player Charlie Davies scored a very interesting goal. Davies scrambled toward the ball and found himself very close to the goal at the end of the field but with no direct shot because an Egyptian defender was in the way and there wasn’t a big enough of an angle open for Davies to shoot it past the defender. Then, as the Egyptian goalkeeper comes back towards the goal and rushes toward Davies, Davies intentionally shoots the ball away from the goal and toward the goalkeeper. The ball ricochets off of the goalkeeper and goes into the goal. It’s sort of unbelievable. And beautiful. If you asked most people how to score a goal, they’d say something like “you kick the ball past the goalkeeper into the goal”. And that is how it happens most of the time, but that description assumes quite a lot: it assumes that you kick the ball instead of use your head or shoulder or stomach or back; it assumes that you aim at the goal rather than away from it; and it assumes that someone on your team is scoring the goal when it could be someone from the other team scoring on itself. Or the wind could blow it in. For a goal to be counted, there is only one thing that has to happen: The ball must cross the line.

Tip: Describe your problem broadly to other people who can help you solve your problem.

Thinking of your problem broadly will help you solve it. Letting other people know the broadest version of your problem will help them solve it best. If you want to hang a picture on the wall, don’t go to the hardware store asking for a hammer and a nail and some string. Go to the hardware store and tell them that you want to hang a picture on the wall. Because they might give you a hammer and a nail and some string, but they might also give you something that you’ve never heard of or seen before, like a monkey hook or a drywall screw. If you go in and ask for a hammer and nail and some string, then all that they can think to give you is a hammer and nail and some string, which might solve your problem but it might not solve it best.

Like it? Share it. Thanks!